An earlier version of this essay was posted in 2014 on Julie Heffernan and Virginia Wagner’s, Painters on Painting, a website I recommend to anyone curious about what artists can sound like when released from incessant calls to spin tales and extenuations around their own work.

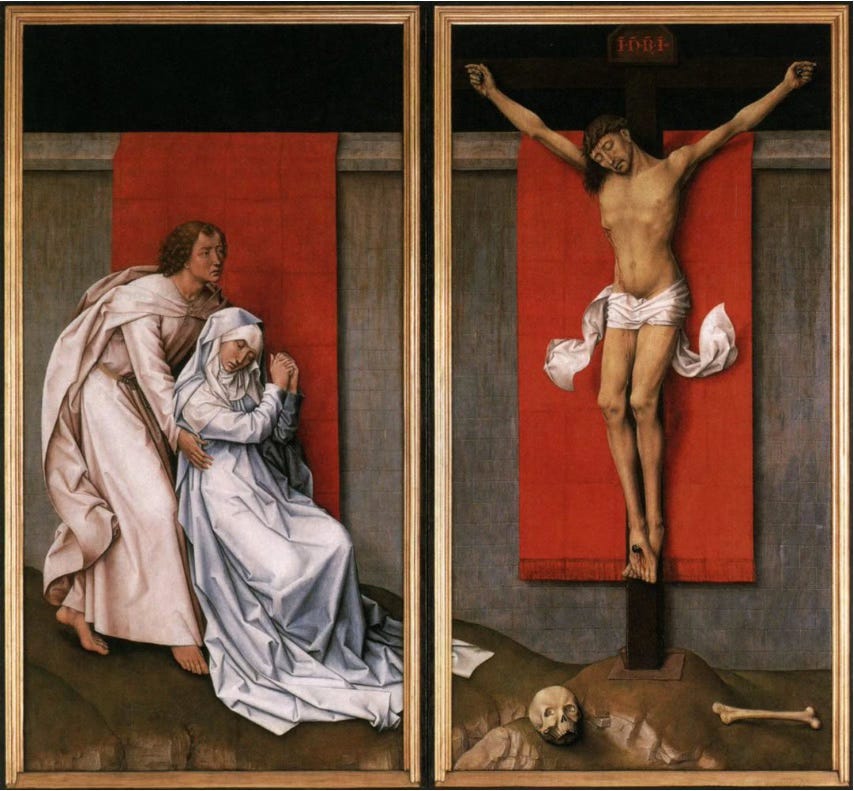

In 1982, I was driving back to New York from a weekend of art museums in Washington DC, when I made a stopover at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It was on that visit that I first encountered Rogier Van der Weyden’s c. 1460 Crucifixion and almost immediately became fascinated by the possibility that the pair of hanging red drapes, one in each of the painting’s two panels, were the same drape. I don’t mean the same drape painted twice. I mean the drapes as a conceptual representation of only one place and only one moment, repeated to suggest the two main figures in the picture, the Virgin and the crucified Christ, were synchronous in both time and space. It was a notion likely born of my having encountered Barnett Newman’s c. 1958-66 Stations of the Cross the day before in the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing.

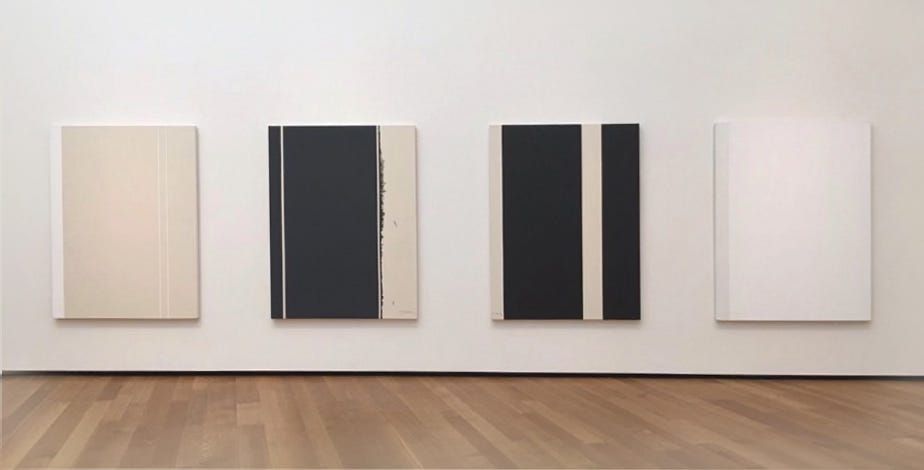

Newman’s Stations are a set of fourteen abstract canvases of identical dimensions, painted in spare divisions delineated with either black or white paint on unprimed canvas, each panel following two predetermined guides. In a statement written for the work’s inaugural exhibition at the Guggenheim in 1966, Newman informed viewers that for him the story of the passion was an expression of a single idea conveyed in words Jesus apparently knew from Psalm 22:1 — “My God why have you forsaken me” — and that according to both St Mark and St Matthew, were the words Jesus cried out from the cross before dying. Newman chose the original Aramaic “Lema Sabachthani” for the subtitle of the series. He insisted that his stations were not episodic but fourteen expressions of that one wretched cry.

What struck me about the Stations that day in Washington—and what informs my reading of the Van der Weyden piece to this day—was how Newman seemed to transform the viewer’s experience into something like Mircea Eliade’s notion of circular rather than linear time. To stand, for instance, before his Eighth Station was to return to the place experienced in his Seventh Station, and so forth. Engaging with one panel, then the next, compels a viewer to enact a ritual return of psychic rather than liturgical repetition.

The Van Der Weyden painting, one of several in which the artist explored aspects of the crucifixion narrative, was acquired by the Philadelphia Museum in 1909 as two unframed panels. Their original configuration was unknown and for decades puzzled the museum curators who were considering many possibilities, including that of a missing third panel. The third panel theory was eventually abandoned and the current arrangement, a diptych in a flat understated frame, was arrived at largely by following the most reliable clue, a corner of the Virgin’s gown that passes across the center framing element.

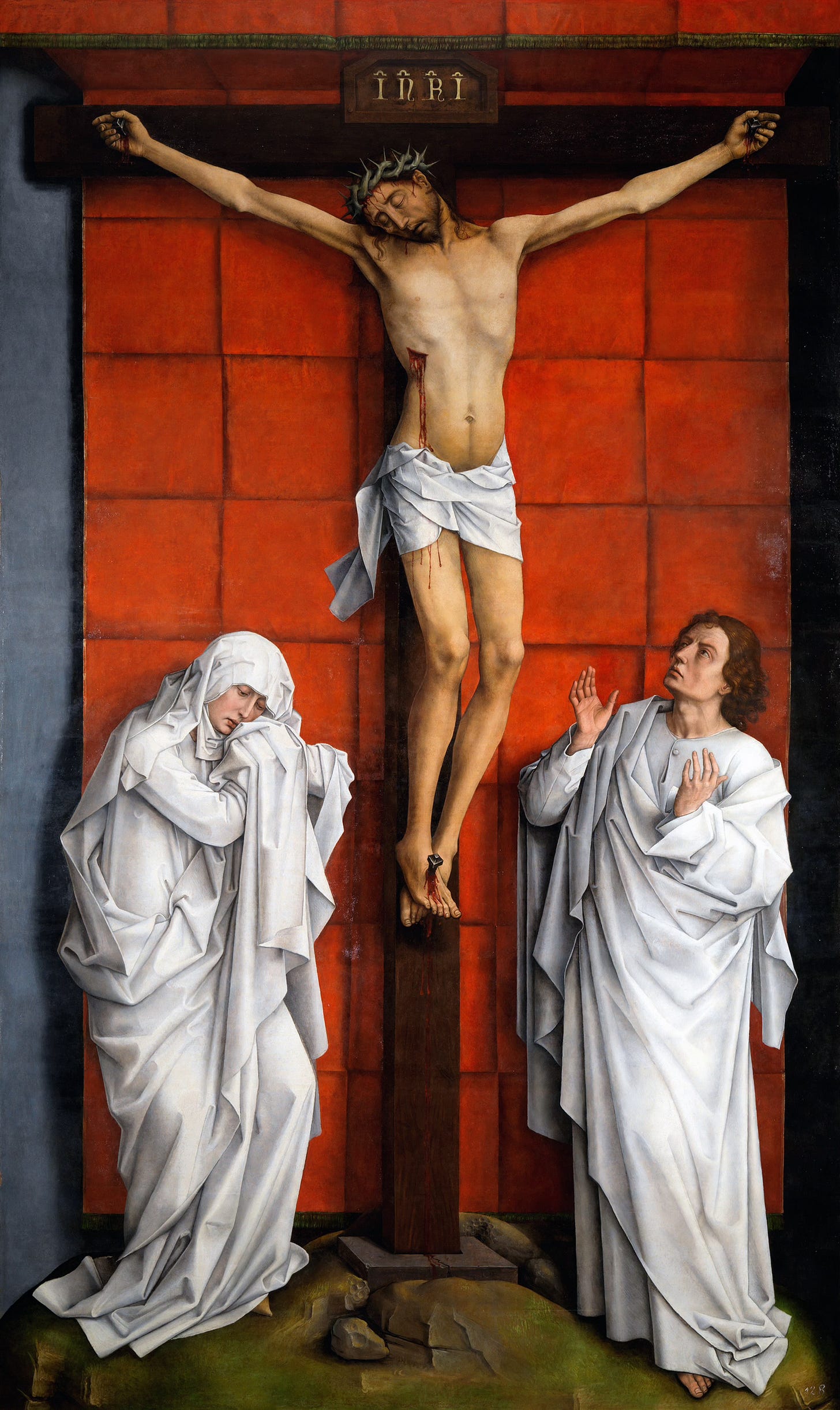

The Virgin’s swoon, as the subject is commonly known, refers to that dramatic moment when Christ expires and the Virgin faints in response, leaving both figures to a simultaneous loss of consciousness—one of actual death (though theologically temporary), the other of emotional synchronicity. It was not unexplored territory for the painter. His much earlier Deposition, now in the Prado, depicts a variation on the swoon in which both Virgin and Christ collapse into curves that choreographically dissociate them from the surrounding figures.

Separating the main figures in distinct panels, as the Philadelphia painting does, puts greater emphasis on the Virgin and Christ’s physical isolation. But why are the drapes separated as well? Both the wall and the ground are painted as continuous. Van der Weyden himself had made use of a single drape in the Escorial Crucifixion painted around the same time as the Philadelphia painting. The background wall in both versions, a reference to the outer wall of Jerusalem, appears in the Philadelphia painting as continuous from one panel to the next, as is the ground, further emphasized, as mentioned, by a corner of the Virgin’s gown.

What distinguishes the Philadelphia painting from the artist’s other versions is that the Virgin and Christ are suspended, both traumatically and physically; the crucified Christ on the infamous apparatus of the cross, the Virgin in the arms of St. John. Though physically discreet, they share a deeply emotional space, an obvious echo of their prenatal history. Both suspended figures align with the central axis of each drape, giving each cloth greater significance that when used to merely introduce a symbolic red background.

Lacking any documentation, I began drawing compositional vectors over the image, searching for an underlining structure that might indicate intention beyond simple compositional balance. After several attempts, one set of lines settled neatly into the artist’s arrangement. Drawing two parallels from the lower corners of the drape on the right panel, across the painting to the lower corners of the panel itself on the left, and repeating the same lines in the other direction, the intersecting lines formed I revealed—no surprise here—a shared cross1. But not so easily dismissed are how those parallel lines respect many subtle elements in the picture’s spatial and figural arrangements.

For instance, the two lines I drew emanating from the right panel emphasize the subtle turn of the figure toward the Virgin, while the lines emanating from the left panel appear to be guides used in positioning the Virgin and her supportive companion. Moreover, the inner line from the right panel seems to mark the edge along which the Virgin’s gown breaks to its horizontal spread across the ground, while its parallel traces the crack in the earth mentioned in Matthew 27:51, “and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent”.

If I’ve discovered any credible support for the idea that the artist was acutely aware of the drapes and their function in the more subtle aspects of the narrative, it would be in these these lines. But that was as far as I got. Writing the extensive twenty-page version of this research was enough for me.2 I went back to painting. Yet I remain firmly invested in the idea that an Abstract Expressionist and a Northern Renaissance master shared in an unusual conceptual premise across four centuries.

Frankly, I wouldn’t be surprised if a scholar proved definitively that my interpretation was wrong. It’s not hard to imagine a diligent researcher uncovering a document describing how a patron had requested separate drapes in separate panels. In the absence of a definitive historical record, what we know of the artist/patron relationship in the 15th century leaves that scenario as probable as any other. Yet my reading could have been the intended reading, regardless of whichever contributor held sway over the final design.

Artists differ fundamentally from academics. Artists need the freedom demonstrated in highly speculative interpretation. That freedom opens new paths of creative expression. Harold Bloom’s notion of strong poets misreading the work of other poets is the only scholarly exploration I’m aware of that addresses this issue, even if he does so vicariously.

Despite the best efforts of MFA programs, the scattershot studio methods of contemporary artists will never fit into an academic research model. As individuals whose profession requires conjuring something from nothing, artists thrive on unsupported intuitive assertion. Which is what makes Painters on Painting such an inspired project.

I’ve suggested many times in my posts that what artists say about their own work is no guarantee that their work’s meaning has been settled. But the very chaos of our interpretive methods can be redirected the other way, and offer unexpected and intriguing perspectives on the art of others.

Von Simson, Otto G. “Copassio and Co-redemption in Rogier van der Weyden’s Deposition” Art Bulletin, December 1953

The version I posted in Painters on Paintings was more like the one you’re reading—a lot shorter than a grad school paper.