Any painter choosing to adopt the streets of New York as their subject will inevitably run headlong into Edward Hopper’s formidable body of work. That challenge was taken up by Lisbeth Firmin whose painterly take on New York debuted on canvas for the first time in 1992, a quarter century after Hopper’s passing. The moody images of that famously irascible tenant of Washington Square North bear little resemblance to the animated scenes Firmin began composing in her Sullivan Street studio just blocks from where Edward and Josephine Hopper lived for five decades.

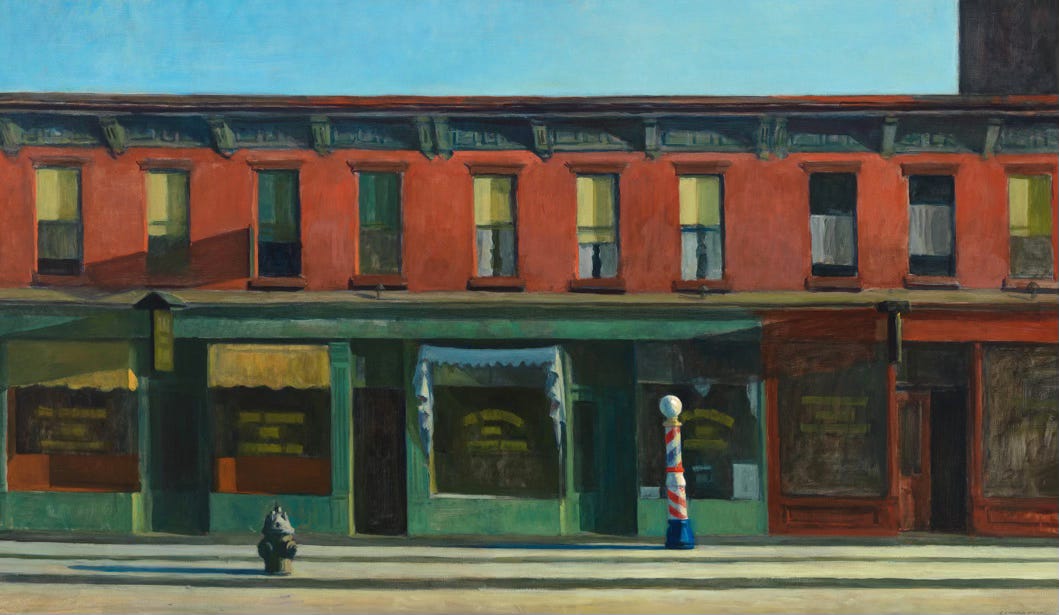

During the Hopper’s New York exhibition held at the Whitney Museum in 2023, a sizable gaggle of us were packed into the show’s modest reserve of the Whitney’s fifth floor, leaving the better part of the museum’s voluminous space empty but for extravagantly spaced examples of post-war painting and sculpture. Crowd size alone demonstrated that Hopper’s vision of century old architecture, deep-set windows, and furtive, uneasy figures retain much of their dramatic appeal. Nostalgia seemed especially vital among viewers, judging from the comments I overheard in the show’s crush. What I took from both listening to and observing those who were obviously too young to have experienced even the mid-century remnants of Hopper’s New York, was that his pictures had become historical fiction. Paintings like Early Sunday Morning suggest Hopper is the Hilary Mantel of pre-war New York.

When I saw Lisbeth Firmin’s work for the first time in 2002, I was impressed by how her painterly skill gave formal support to a very different, immersive attitude toward the streets I’ve walked since I was old enough to take the subway into Manhattan on my own. Firmin’s crosstown vistas do not convey desolation. There are no empty sidewalks articulated by the extended shadow of a lone hydrant. Her lively compositions suggest weekday afternoons and busy evening rush hours. What’s particularly striking is how each painting confirms the artist’s participation in the depicted energy. Firmin is not an alienated witness. She rides the city’s flow along with her actors.

New York is a place where sidewalks have been managed for generations by shopkeepers who sweep the evening’s nostalgia to the curb each morning. Firmin’s paintings confirm this metamorphosis. Her compositions synthesize shape and color into balanced chaos, regardless of whether they are defined by a single figure, or several figures, or a dog, or trucks, or rain, or snow, or the deep shadows of tall buildings. Light unifies the work of both artists, but Firmin’s insatiability devours the whole environment, an environment that may include a slash of sunlight across a shaded alley, or the ephemeral glow of a garishly lit storefront but suggest a great deal more. Firmin replaces Hopper’s cheerless thespians with people that appear alive, quick, and determined to get where they’re going.

Like Hopper, Firmin’s attraction to light began in landscape. And like Hopper, Firmin came to the city from a small town. Unforeseen events in the 1990s brought her to a new and unfamiliar urban routine. She met the challenge by engaging with the inevitable contradictions the city imposes on newcomers. Surrounded by shifting visual stimulus, it became clear to Firmin, by the 1990s an already a committed painter, that setting up an easel on the sidewalk was not going to work. The camera became an indispensable tool for bringing the raw material to the studio where she invented a compelling visual language capable of rescuing what a camera can rarely detain.

Muting the noisy details photographs invariably produce, her painterly shorthand reduces each scene’s complexity to essentials. With a photo pinned to the easel, she begins each picture by blocking in foundational color with a large brush. Smaller brushes are gradually introduced as the painting evolves. Light becomes a medium. Light that allows rain-doused crosswalks to amplify the effect of a vehicle’s shimmering headlamp. Every recognizable thing in a Firmin painting is of the atmosphere enveloping it.

I’m especially taken by a panel from 1997 titled, “Grand Central, Lexington Avenue Exit”, posted at the top of this essay. The compositional order of this picture is so infused with the air of a sodden commute that it takes time to notice two distinct and most likely unplanned style adaptations. A very loose yet oddly geometrically structured composition echoes the work of both Fairfield Porter and Piet Mondrian, incidently two more rural transplants to Manhattan. A pair of yellow reflections frame the lower half of the picture, in counterpoint to the blue mass of the upper left and right. A line of commuters in silhouette bridges the left to the right with both Mondrian clarity and Porter-like brushwork. The artist had to step into the street to record the visual fundamentals of the scene, which illustrates Firmin’s ability to quickly engage with a complex pictorial idea then return to a participatory perch she requires. An afterimage of remembrance is then reconstructed days, sometimes months later, in the solitude of the studio.

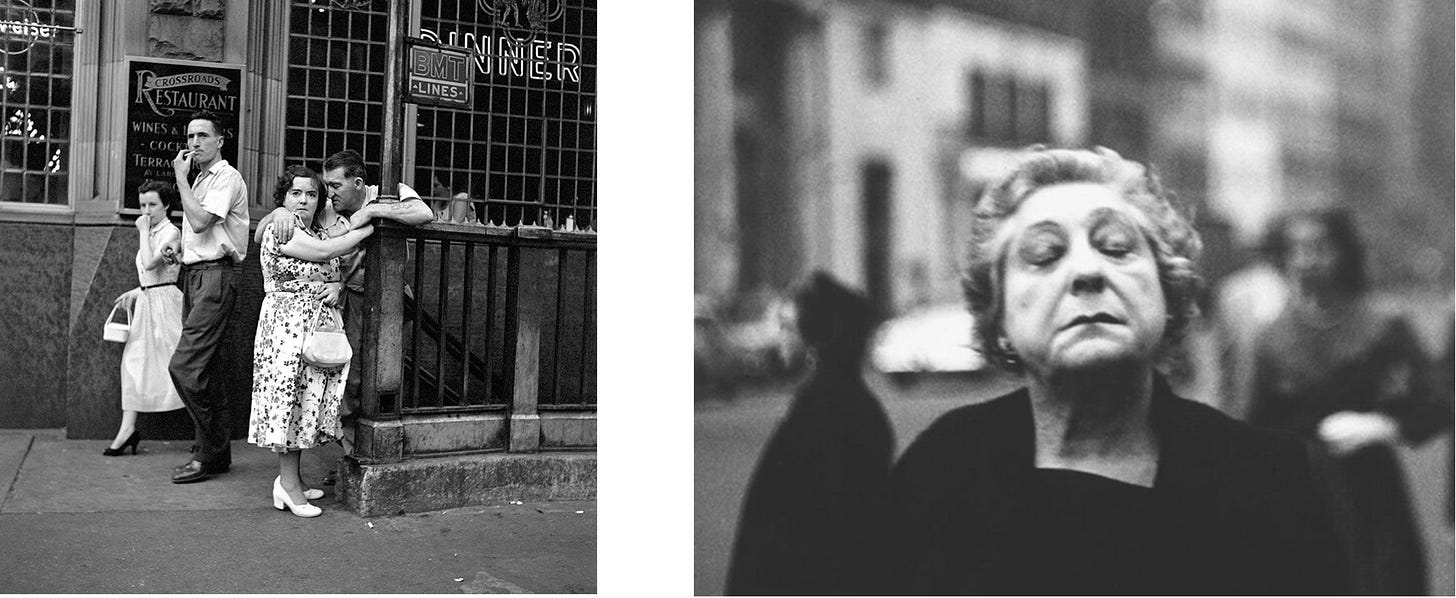

The spontaneous character of such moments may suggest an affinity with the art of street photography. The difference is that most street photographers, Vivian Maier or Diane Arbus for instance, are stalkers. They seek pictorial collaborators, spontaneous performers, individuals who break the routine. Figures out of synch with their surroundings. Firmin’s concern is with how it all fits together. And to assemble that puzzle requires a painter’s studio and the time to ponder that a studio offers and that a shutter denies. Absolute solitude, brought to bear on a moment defined by the interaction of so many moving parts, including the artist’s memory of the moment, resembles juggling more than capturing—gathering more than hunting.

Firmin and Hopper’s paths ultimately align in that space where an individual commits to what they alone experience. Hopper’s genius was in constructing a vision of New York that intoned his cranky, plaintive nature. Firmin’s perspective is lively and sunny, and so is her New York, even when it’s drenched in an inconvenient downpour. Many things can be true at the same time in a large city.

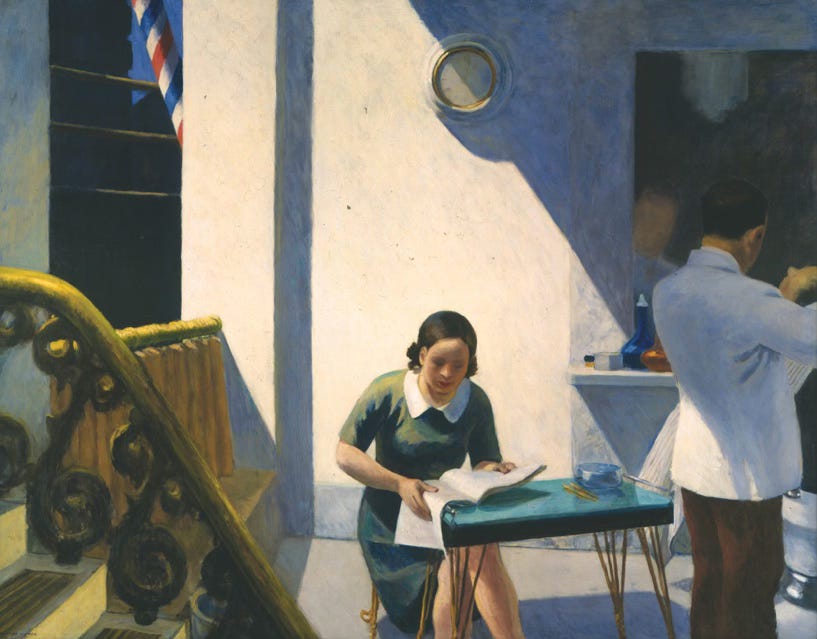

It’s important to note that Firmin’s panels rarely exceed forty inches in either direction. They offer fleeting moments, enhanced not only by her painterly agitation but by the concentrated density of a panel that allows only one well placed viewer at a time in a gallery setting. Though Hopper remains in the easel category of mid-century American painting—militantly so, as he picketed the Whitney Museum with Milton Avery against Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s—his dramatic staging and carefully chosen programmatic elements justify his work’s comparatively larger dimensions.

I’d urge a reading of Bryan Robertson’s essay in the December 1971 issue of the New York Review of Books in which he explores Hopper’s relationship to theater. I am reminded of this essay every time I return to Hopper’s “Barber Shop” at the Neuberger Museum. At 78 x 60 inches, it is his largest canvas Hopper ever painted and serves as a reminder that regardless of their celebrated silence, Hopper’s compositions are like arias meant to reach the upper tiers.

Firmin’s are more like songs heard on the radio. Received as if the listener is the only member of the audience.

Lisbeth Firmin, Edward Hopper, and New York City, is an expanded version of an essay I wrote for Firmin’s recently published monograph, “Lisbeth Firmin: Working the Light”, available on Amazon.