Harvey Dinnerstein and the Figurative Dilemma

June 6 - July 13, 2024, Art Students League, Phyllis Harrison Mason Gallery, NYC

“…and they moved across the bridge to Brooklyn Heights, a few minutes from his studio on Front Street … but as everyone knows, the East River separates you from the center of things as decisively as the Rocky Mountains.”

Thomas Hess wrote those lines for the Museum of Modern Art’s 1971 Barnett Newman retrospective. The biographical arc Hess devised for the catalog pivots dramatically on this third plot point, this tragic interlude when economic difficulties in 1956 exiled Newman and his wife Annalee to the worst possible place —Brooklyn Heights, a section of ersatz New York that any top tier Abstract Expressionist of the period would have shuddered to contemplate.

In 1928 Harvey Dinnerstein was born in Brownsville, a deeper Brooklyn neighborhood, a neighborhood several miles east of where Ebbets Field stood, let alone the East River. In 1961 he settled his young family in Park Slope where he established what was to be his studio for six decades.

From this address, Dinnerstein produced a body of work tapped over the years for the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum, the Museum of the City of New York, the Butler Institute of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the National Academy of Design, and many others. Yet his name didn’t even rate a casual mention in New Art City, Jed Perl’s 2005 tome on the history of the New York art world. Dinnerstein passed away in 2022 ending a prolific career notable for its extraordinary lack of coverage in the New York art press.

Dinnerstein’s apparently made modernists uncomfortable. A sizable portion of his work makes me uncomfortable as well, though I find this discomfort intriguing. It raises questions, implies presumptions and reveals biases we take for granted even in this new century. Fortunately, at the Phyllis Harrison Masion Gallery, located on the second floor of the Art Students League on West 57th Street, an apt venue as Dinnerstein taught classes there for decades, the public can decide for themselves if he’s been treated fairly or has been understood as fully as he could be.

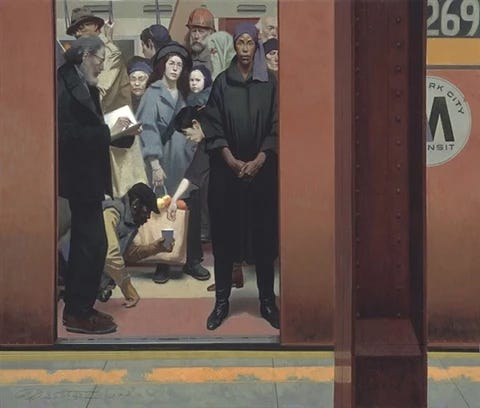

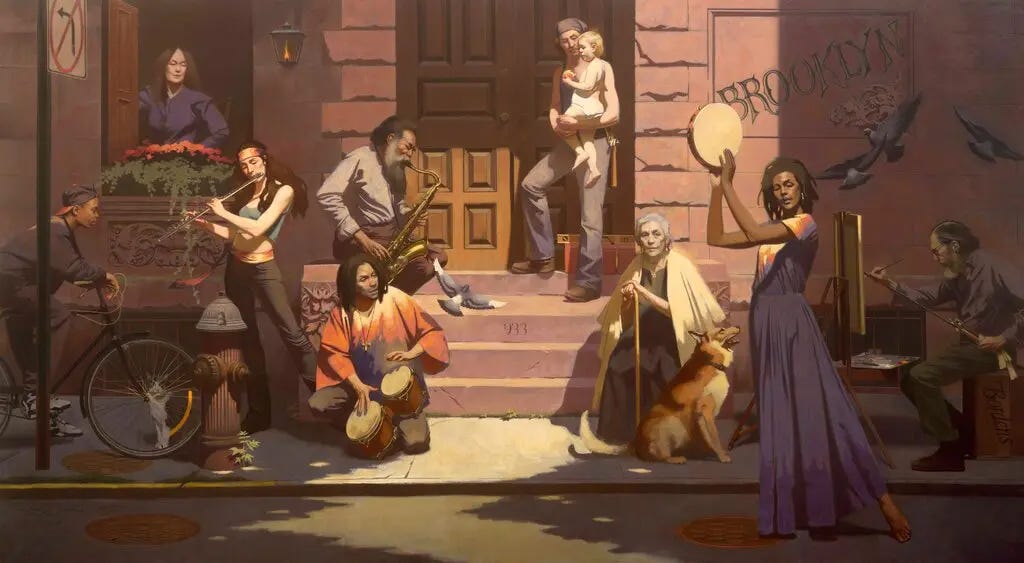

Brooklyn, especially the residents of Brooklyn, were Dinnerstein’s subjects. There is a direct, plain spoken character to his paintings of neighbors, street scenes, and the architectural features of nearby Prospect Park. But that Robert Frost common touch often clashes with a Walt Whitman licentiousness. A great dissonance sounds when those conflicting tendencies meet, as they do in his heroically scaled allegories.

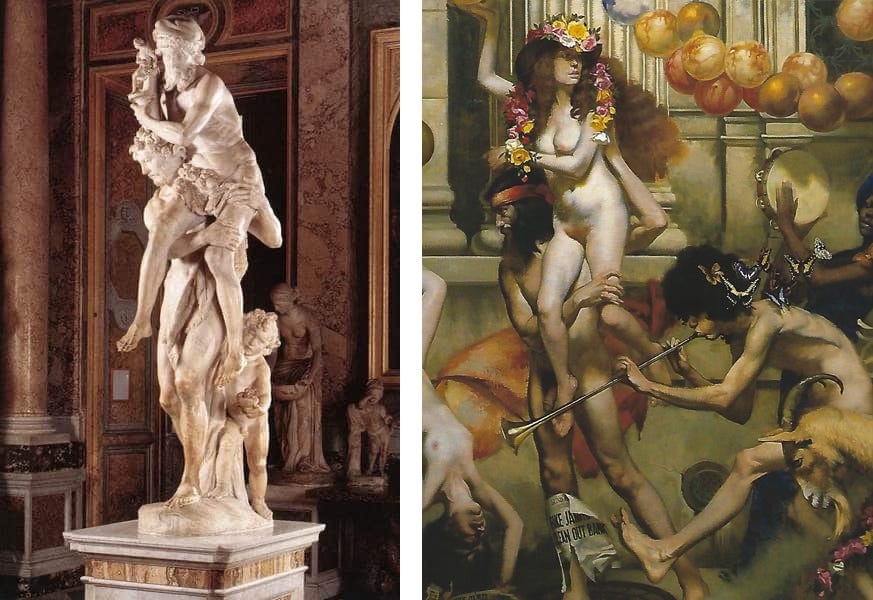

In speaking of one ambitiously epic canvas, Parade completed in 1971, Dinnerstein explained what he hoped would be…

“…a procession related to Ruben's wild bacchanalian images. As the painting evolved, I combined and expanded various elements… [I saw] a young man carrying a woman on his shoulders at one of the [anti-war] demonstrations and I tried drawing a couple in my studio in a similar position this seemed unconvincing until I remembered a drawing I had done in an old sketchbook of a Bernini sculpture I had seen in the Museum Borghese …”

The sculpture in the Borghese was Bernini’s Aeneas and Anchinese, a marble depicting two male figures, one carrying the other, that served as the inspiration for Dinnerstein’s male and female studio models positioned on the left of the composition. Those models are rendered masterfully in the final canvas. But his mention of Rubens and Bernini as the measure of what he intended implies a dynamic that for a number of reasons failed to materialize in the finished work. First, Aeneas and Anchinese was a poor choice for a “convincing” pose. Its a very early Bernini with none of the theatrical flair we associate with his later Apollo and Daphne or the St Theresa in the Cornaro Chapel. Second, the pose Dinnerstein assigned to his studio models is more life drawing 101 than “bacchanalian”. And third, by overlaying these stiff sculptural avatars with a running male straight out of a Norman Rockwell boys-will-be-boys scene, the attempted fusion stalls. Too many signals coming from too many directions.

Its indicative of a problem in contemporary art that gets little attention. When an art student displays outstanding talent, when they demonstrate they can actually see, draw, and paint with exceptional skill, they’re eventually escorted separately by partisan instructors to a metaphorical fork in the road. One path suggests they not only embrace the art of the nineteenth century but wear it proudly on their sleeve, like Dinnerstein and the eccentrically academic Jacob Collins. The other path suggests our gifted student develop a mannered ambiguity, like that of Neo Rauch, or worse, embrace their id as Lisa Yuskavage did with considerable success. The former urges a reactionary reading of art history, peppered with glib comments about the classics, while the latter counsels ambiguity and provocation, the Beluga caviar of the art market.

Dinnerstein’s allegories definitely align with the former. But unlike the fussy, polished Collins, Dinnerstein often strays from his declared aesthetic positions toward a tasteful understatement. It’s especially true regarding his portraits. These pictures stand out precisely because they don’t rely on a self-conscious skimming of art history flotsam. In a room with a model, Dinnerstein shines. Here he can hold his own against contemporaries like Sharon Sprung or Kehinde Wiley.

A portrait titled, Althea strikes a subtle balance between the graphic simplicity of her rendered garments and the sculptural complexity of her face, the two harmoniously joined by the subject’s partially raised arm, realized as economically as any Manet figure I can recall. This portrait of a neighbor says so much more about Brooklyn than Dinnerstein’s overwrought allegories or sentimental street scenes.

His motivations are not hard to see. The Brooklyn that Barnett Newman judged a prison is the Brooklyn Dinnerstein loved and apparently felt needed defending. That battle ended a long time ago. Most of the artists in New York today actually live in Brooklyn. Hyperallergic, the Brooklyn Rail, Bomb Magazine, all have their offices there. Manhattan may still be the epicenter, but most artists can’t afford it.

The lesson I took from the Dinnerstein exhibition is that the real Brooklyn, the Brooklyn Dinnerstein knew intimately, is still there. It comes alive in his portraits. He would never have achieved even that modest success had he been a mediocre talent. This is where the discomfort many of us feel with his work comes from. It’s not him. It’s us. What we demand of our artists these days emanates from the top down. Both the voracious art market and the overconfident university art department make it difficult for a painter of Dinnerstein’s independence to fit in. And after studying his work closely, I’m still uncomfortable with much of it, which leaves me wondering if I’m too sophisticated, or too jaded. Or is there any difference between those common art world maladies.

Please note, if you wish to leave a comment on any post, I prefer you send it directly to: