Authenticity vs. Ethylene Polymer

Studio furniture, iconic movies, and the clarity that never comes.

1.

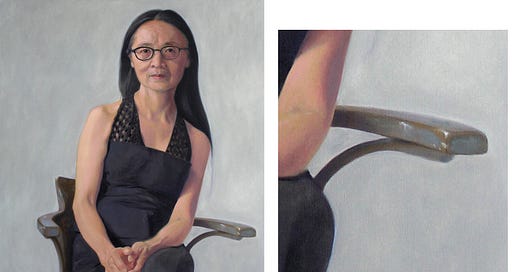

In composing a portrait of artist Ying Li a dozen years go, I suggested she sit on an antique tavern stool that was clearly a valued item in her studio. The chair’s wrap-around arms showed signs of wear. The original varnish was almost gone and carelessly spotted with accidental drips and smears of fresh paint. The former was a sign of the chair’s age, the latter was evidence of the artist’s labor. I felt rendering such clues prominently was essential for a portrait of a professional painter.

When I recall the stuff artists bring into their studios, aside from their supplies, I am reminded of the old chairs and other relics of bygone craftsmanship that seemed both used and treasured in their new home. And I wonder if what attracts artists to these objects are their hand-made properties, or their discarded status. Perhaps it’s a combination of both. Seeing the chair in Ying’s studio suggested a metaphor pertaining to the contradictory realities of a painter’s profession. And old and once venerated art form that has grown as thin as old varnish but endures.

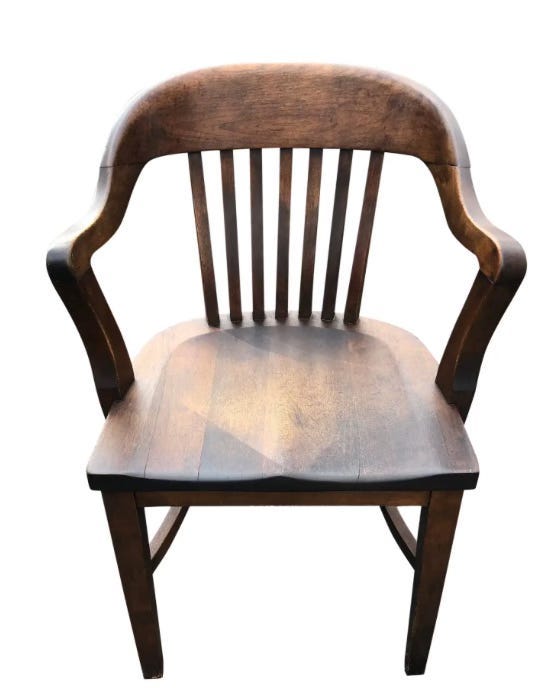

Ying’s stool is actually an outlier. The more common species of antique art studio furniture is the classic “bank” chair.

What had been a popular design for business establishments in the nineteenth century held its own among the green eyeshades and shirtsleeve garters of Bartleby’s world until the 1950s when the post-war business population embraced modern architecture and design. Oak bank chairs slowly gave way to Bauhaus understatement. Hundreds of bank chairs ended up in used furniture stores, hence their reincarnation as inexpensive studio comforts. But why these chairs among all those even cheaper alternatives in the used chair section?

Apparently, there’s something genuine about them. Their consistently worn surfaces are as revealing of their survival as tree rings. And the odd combination of rescue and abuse they suffer at the hands of artists suggests a camaraderie of sorts. Both chair and painter share roots in the past and are willing and able to absorb whatever life throws at them. In a word, both are authentic. And in a profession that presumes its purpose is to seek truth, it’s no surprise that for an artist, authenticity is the measure of everything, even studio furniture.

The downside of presumed authenticity is that artists believe they exist astride the prosaic. A contemporary artist’s often radical sense of autonomy is what leads the public to suspect they’re too self-absorbed. And let’s face it, we are self-absorbed. It’s where we believe our strength lies. For many of us, a sense of being inherently apart is what motivated us to become artists. It’s not always talent. There are young people with considerable talent that choose living conventional lives dedicated to business, science, or some other field. Artists rely on their talent but not as much as they rely on a feeling of being special, separate, apart from the average individual. From this distinctly modern conceit develops a feeling of superiority that is susceptible to both self-delusion and external manipulation.

2.

This tortuous line of thinking has been part of my daily routine for more than a decade. To counter it, I’ve been retracing the steps I took to become an artist. I want to know why I persist in this odd profession. The bank chair in my own studio has lately come to suggest the symbolism of a white elephant—a unique and exotic gift that sooner or later saddles its owner with its endless and all-consuming appetite.

In December of 1967 I sat in a theater watching The Graduate, a comedy by director Mike Nichols, that left a vivid impression on me at the time. I especially remember a scene in which an older man confides with the title character, a young baccalaureate named Benjamin, at a party thrown in the young man’s honor.

The dialogue went like this:

I just want to say one word to you - just one word

Yes, sir.

Are you listening?

Yes I am.

Plastics!

I thought it was hilarious. And I was not alone. What became for many baby boomers an iconic exchange between generations had an obvious message—in retrospect maybe too obvious. It was clearly meant to steer the audience toward a then popular notion that people under thirty held values opposite those held by people over thirty. The recently graduated Benjamin Braddock’s comically deadpan response to an insider tip proffered by the older Mr. McGuire was understood by the under thirty cohort as an expression of moral resistance. We got the joke. I got the joke. I knew what Benjamin’s polite silence meant in the face of Mr. McGuire’s shallow advice.

The older man’s suggestion would probably sound inconsequential to a young audience today. But in 1967 promoting plastic was a culturally loaded idea. Convinced of Mr. McGuire’s cynical and wrongheaded advice, we saw no value in investigating the etymology of the word itself. Plastic predates the stuff our frisbees were made of by millennia. From plastikos, Greek for “capable of being molded”, it originally meant malleable, pliable, kneadable, (flexible?) and remained so until the twentieth century assigned it several new functions. It gained an industrial specificity as ethylene polymer, a chemically wrought substance that could be inexpensively shaped into anything. And when it was shaped into fake leather, fake wood, and fake glass, it was transformed again into a euphemism for superficiality. Because the scene was early in the film’s first reel, the plastics joke nailed its generational message.

Those few potent lines of dialogue were composed by script writer Buck Henry, who was chosen for the job of adapting the 1963 novel into a film script for director Mike Nichols, who felt Henry’s comic sense and Benjamin Braddock-like privileged Connecticut background—Choate and Dartmouth—was a perfect fit. The plastics scene Henry wrote into the narrative was the only significant addition to an otherwise faithful rendering of Charles Webb’s novella, faithful but for a number of interesting omissions.

Even a novel as short as two-hundred and thirty-eight pages requires compression if it is to be transformed into a film of less than two hours. But some omissions were more than pragmatic. Henry and Nichols gave Benjamin Braddock quite a makeover. Consider these two versions of another early exchange between Benjamin and his father.

Buck Henry’s script:

What is it , Ben?

I'm just…

Worried?

Well…

About what?

I guess about my future.

What about it?

I don't know. I want it to be…

To be what?

Different.

Webb’s original version:

Now what is it, Benjamin?

I don't know.

Well something seems pretty wrong.

Something is.

Well what?

I don't know but everything—everything is grotesque all of a sudden.

Grotesque?

Those people in there are grotesque. You’re grotesque.

Ben!

I'm grotesque. This house is grotesque.

Actor Dustin Hoffman played Benjamin just as the film script molded him: an awkward inarticulate but well-meaning nerd. In contrast, Webb’s Benjamin was often aggressive and comfortable dishing malicious characterizations and insulting innuendo. Here’s another scene from the novella that would have undermined the lighter comic tone Nichols and Henry were creating:

“Ben I—I want to talk about values.” “Something.”

“You want to talk about values”, Benjamin said.

“Do you have any left?”

Benjamin frowned, “Do I have any values,” he said.

“Values. Values.” He shook his head.

“I can't think of any at the moment, no.”

“How can you say that son.”

“Dad, I don't see any value in anything I've ever done. And I don't see any value and anything I could possibly ever do now. I think we've exhausted the topic. How about some TV?”

Drawing the humor from each of Webb’s carefully composed scenes and filtering out the shrapnel begs interesting questions. Was Benjamin an idealist rebelling against his pampered background? Or was he a predictably narcissistic product of that same background? The New Yorker’s film critic Pauline Kael caught this dilemma early on. She wrote:

“…comic moments click along with the rhythm of a hit Broadway show.” […] “But then the movie deliberately undercuts its own hip expertise and begins to pander to youth.” […] the graduate stood for truth; the older people stood for sham and for corrupt sexuality. And this "generation-gap" view of youth and age entered the national bloodstream…”

Kael’s minority analysis reads today as sound. Though I’d add that her suggesting the film launched the generation gap is as hyperbolic as the plastics scene itself. I remember vividly that a wide gap was already there, though I can now see how the film exploited it. I graduated high school in 1968, perhaps the most conflicting year in a decade of upheaval. Making sense of the generation gap from here in this new century leaves me wrestling with many unresolved puzzles.

For instance, on several occasions I witnessed members of my father’s generation, specifically veterans of the Second World War, express undisguised loathing toward anti-war protesters. Yet I watched several of those same men take extraordinary measures to get their draft age sons into the reserves and out of danger. The older veterans had been ordinary soldiers who had fought what Studs Terkel called “The Good War” but learned to be skeptical about their commanders. With their responsibilities now extended to adult children not yet born during their service, what they remembered was an inherent distrust of the military’s motives. They were on both sides of the anti-war argument, passionately so. But only one side was shown in public. It’s notable as well that the film never mentioned the war.

What the book and the film versions of The Graduate reveal is that Benjamin Braddock sought clarity. Autonomy it seems is as close as we ever get to clarity. Nichols and Henry proposed the clarity of a dopey innocent, reminiscent of Voltaire’s Candide. Webb’s Benjamin was closer to the frustration and the quick anger I saw in my peers in the 1960s. Both have a measure of truth, but the greater measure of clarity is in their unresolved divergence.

3.

A commitment to painting as a career provided clarity in my life. But that clarity grew foggy as the years went on. The art world I joined changed so many times that today I barely recognize it. Authenticity, or something resembling it, has been sculpted by the art market into a branding exercise. Dealers and curators have grown adept at shaping it, forming it, and molding it to fit their needs. I maintain my original ideals, but I see them losing their importance. I’m left with more questions than answers. Do I paint just for myself? What does that even mean? How much attention should I pay to a viewer’s perception? Am I capable of critiquing my own motives? Does a painting have any real value if no one else sees it?

Autonomy does not come easy. For any artist, finding one’s unique voice is as long and as arduous a process as identifying one’s values. In many ways they are the same thing. In my own experience I did not decide to be an artist so much as I decided not to be the alternative, which explains my getting such a kick out of Buck Henry’s joke sixty years ago.

I now have as much clarity as I believe I will ever have. I’m learning to live with the dilemmas and contradictions of my profession. I am content in my life and in my studio. My studio has everything I need. Lots of paint. Brushes appropriately pampered and abused. Yards of canvas. An easel that adjusts without too much fuss in a room full of sunlight most of the day.

And a bank chair in the shape of what was once the throne of a depression era loan officer and gatekeeper of commerce. Perhaps a man who hated modern art. I sit in this chair and assess my latest paintings. I’ve had it since the early 1990s. But mine is not the typical bank chair. It bears no visible wear and tear because it’s not made of old varnished red oak.

Its plastic.

Bravo peter